Can LLMs help us to agree?

LLMs are addressing long-standing issues of consensus, but there are many risks.

And they haven't given us any other options outside the occasional, purely symbolic, participatory act of voting. You want the puppet on the right or the puppet on the left? I feel that the time has come to … let my own lack of a voice be heard.

(He pours gasoline all over himself and lights himself on fire.)

The Burning Man from “Waking Life” (Richard Linklater, 2003)

For many reasons, around the world, trust in representative institutions has been in steady decline for decades (e.g. this for US, this for UK). In general, people still value democracy as an idea, but lack faith in the institutions that administer it. Small wonder, then, that movements aiming to tweak or improve democratic processes are gaining momentum, especially those that emphasise more direct participatory models, and now that shift is being boosted with AI.

Direct participatory models create opportunities for participants to influence the decisions that affect them, typically through some process of deliberation that leads to a consensus position that aims to satisfy the as many people as possible to the greatest possible extent.

This is a concept that stretches back to ancient Greece, and has been addressed by historical figures ranging from Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Stuart Mills, Jurgen Habermas, William Riker, and in the 21st century Audrey Tang, Glen Weyl and others, and is now entering its AI-era, which brings profound opportunities and also risks. Today the philosophy and practice of participatory democracy are evolving faster than ever, driven by a crisis in trust, a need to coordinate around increasingly complex challenges and new forms of technology including AI.

I’m interested in exploring this space not only because it’s inherently interesting and important, but to see what principles can be adopted to improve and scale distributed decision-making at organisations like the Green Software Foundation.

Historical foundations

Direct participation was a feature of Athenian democracy in the 5th century BC. Citizens would gather in the Agora to come to decisions directly, not through representative politicians. Key political leaders were appointed by random selection from the citizens (sortition). However, only a small subset of the population were included in the democratic process (e.g. no women, no slaves). Much later (1700s), Jean-Jacques Rousseau established The Social Contract, which asserted that political legitimacy can only arise from the general will of the people being governed, distinguishing the collective good from the wills of individuals. He was highly sceptical of representatives and insisted that direct participation is necessary for legitimate democracy. He also believed that democracy was not very scalable and only worked in smaller communities. A key tension for Rousseau was how to distinguish the true general will of the people from majority tyranny (a tension that persists to the present day). Countering majority tyranny is the intended purpose of constitutions, separation of powers, individual rights and other check and balances in government today. In the 1800s John Stuart Mill commented that the competence of the participants is an important factor in participatory democracy, as uninformed participants might be less likely to make decisions that are truly aligned with their needs and might be more easily manipulated. The quality of discourse and deliberation was recognised as being key for effective democracy.

Modern theories

At it’s core, democracy is about finding consensus. Consensus is a widespread agreement among a group. In the 1900s Jürgen Habermas considered the possibility (but not certainty) of consensus - authentic agreement reached through reasoned dialogue and deliberation - under ideal conditions. Those ideal conditions include the ability to freely question any assertion, enter any position into the discourse, and express any view without hesitation, which amount to freedom from coercion. Habermas suggested that, under these conditions, a legitimate democratic decision could be achieved through deliberation, an idea known as “communicative rationality”. Habermas also pointed out that discourse alone does not guarantee agreement - often there will be conflicts of interest to handle, impasses and incompatible views that have to be handled through compromise or majority vote. He also suggested that compromise is typically formed inside political institutions, informed by a plurality of positions that are voiced in the public sphere (i.e. continuous dissent), rather than participants themselves reaching agreements through direct deliberation. Nevertheless, the ideas of consensus through deliberation are connected to Habermas.

Communicative rationality was challenged by a parallel philosophy of strategic rationality - the idea that actors will game any system according to their own incentives, rather than by a collective will to reach compromise positions. William Riker was a key voice in strategic rationality, who saw consensus as inherently arbitrary and manipulable. He viewed the outcomes of any electoral process as meaningless and unavoidably unfair, for several reasons including Arrow’s impossibility theorem which posits that a fair democratic process must conform to a set of conditions that Arrow proved to be violable. Riker saw participants much more as strategic agents with their own incentives than altruistic agents aiming to compromise, echoing modern game theory. While Habermas saw institutions as bearing responsibility for creating conditions for ideal speech, Riker saw institutions as exploitable agents that influence outcomes at least as much as individual preferences do, and considered outcomes to be fundamentally dependent on how choices are structured and presented to participants. He even coined the term “heresthetic” to describe the “structuring of the world so you can win”. Overall, while Habermas believed in true consensus, Riker viewed any consensus position as a temporary equilibrium brought about by external factors other than the aggregation of individual preferences, that is vulnerable to change. It should be noted Riker’s arguments have been challenged and several of the historical examples he used to support his theories have been discredited by e.g. Mackie (2003).

Social choice theory intersects with the work of Habermas and Riker, but is distinct in that it presents a specific mathematical framework for aggregating and representing individual preferences. It focuses on the mathematical properties of voting rules and patterns. Riker used social choice theory as evidence against the efficacy of democracy, while Habermas considered social choice theory to be a distraction from what he thought was the main point - communication and compromise.

Modern models of participatory or deliberative democracy have focused increasingly on plurality (multiple ideas and authorities coexisting) and conflict as routes to deep engagement with issues that ultimately lead to agreement, partly as a reaction to earlier forms of deliberative democracy being increasingly assimilated by the establishment authorities it originally aimed to challenge (e.g. Dryzek, 2002).

Today, the field of digital democracy has emerged to address the various paradoxes and impasses of participatory democracy using technology. The ideal is to create a synthetic approach that somehow incorporates the mathematical rigour of social choice theory, Habermasian ideals of communicative rationality, and awareness of strategy, incentives and manipulation. Digital tools aim to use the inherent scalability and agility of software and the internet to map preferences and preserve complexity to a far greater extent than has been possible before.

Early examples of digital democracy tended to focus on lowering barriers to participation and scaling communications, making use of forums, online surveys and petitions, email campaigns, etc. However, to a large extent this was really just a digitisation of traditional analogue systems. Later, more sophisticated platforms emerged which included functionality that leaned more heavily into the online world to scale quality discourse. The standout example is Pol.is - a purpose built platform for democratic participation where users discuss and vote on statements and an algorithm clusters opinions into groups.

A key innovation is that direct replies and responses to other participants’ statements is prohibited, avoiding trolling and flame wars, and instead users submit short independent statements that others can agree, disagree or pass. A clustering algorithm groups participants in real time and creates visualisations of opinion clusters, areas of consensus and disagreement. This process has been deployed several times in the real world, most famously in Taiwan, where the vTaiwan platform has been used to find consensus solutions to issues as diverse as regulating Uber, e-scooters and fintech. One of the big benefits of a platform like Pol.is is the amount of sophisticated operations that can happen in approximately real-time. It can work across multiple languages, devices and user interfaces. It enables “listening at scale” and can algorithmically prevent minority views from being lost in noise. Participation requires engaging with the views of others because participants vote on others’ statements. The algorithm can surface the existence of “silent majorities” who might stay hidden in other forums. However, Pol.is has not escaped criticism, especially from commentators that consider reports of Pol.is’s successes to have been overblown.

New technology is also being used to bridge between previously incompatible forms of governance, for example “liquid democracy”. Liquid democracy addresses the issue that participants only have limited capacity for engaging with issues and quickly reach decision fatigue. Liquid democracy enables participants to engage directly with issues they resonate with or care most about, and delegate their voting power to a trusted intermediary for issues that are more peripheral for them. This is a commonly used protocol in blockchain governance, especially for decentralised autonomous organisations (DAOs). This is also the context where more nuanced voting algorithms are being tested, especially quadratic voting (QV). Pioneered by researchers including Glen Weyl and popularised through the RadicalxChange movement and DAOs such as Gitcoin, QV provides participants with voting credits that they can spend to signal support on issues they care about. A quadratic weighting formula is used to quantify support for an option - one credit is “weighed” as one vote, two credits are weighed as four votes, three credits are counted as nine votes, etc. This has also been used to more fairly distribute grant money to projects according to donors preferences, e.g. in Gitcoin grants. There, a matching pool is used to quadratically weight the overall amount of money allocated to a project according to the distribution of donations it received. The more individual donations a project receives, the more funds are allocated from the matching pool, preventing the system from being overwhelmed by individuals with lots of capital to spend. These are two examples of ways that technology might be able to tame the game theory and strategic manipulation of voting systems described by Riker (although QV-powered systems have been ruthlessly manipulated by e.g. Sybil attackers for financial gain).

AI-powered consensus

LLMs are taking the idea of digital democracy to another level. Whereas Pol.is is limited to voting on predefined statements, generative approaches can create novel compromise positions from unstructured text, i.e. chats with participants. AI is shifting the whole process from collection and aggregation of preference information to real time generation of new compromise statements on-the-fly, using free-form natural language interactions with participants. Before AI, the system could only surface participant’s views on the specific thing they voted on, but with AI participants can explore an infinite possibility space, extrapolate from responses to positions, predict how users will respond to unseen issues, act creatively with response data, build up understanding through iterative rounds of deliberation, and do all this over millions of interactions. The idea is that this can escape Arrow’s and Riker’s constraints - the foundations of the system are just different.

There have been several experiments with LLM powered consensus over the past couple of years. The introduction of LLMs into social choice theory has led to the emergence of “generative social choice” - a theoretical framework that “combines the mathematical rigour of social choice theory with the ability of LLMs to generate text and extrapolate preferences”. The overall aim is to overcome the limitation of social choice, which can only handle finite, predetermined options, by enabling the discourse and the outcomes to be open-ended and perhaps unforeseeable. Also, LLMs allow participants to express their preferences implicitly and indirectly, with the LLM being able to uncover hidden preferences and extrapolate preferences across different contexts. This also means the LLM can act as a proxy for a participant, predicting their most likely preference based on their previous interactions. Generative social choice aims to apply formal guarantees of fair representation, for example using balanced justified representation (BJR) to ensure a proportional representation of different viewpoints is fed into the LLM.

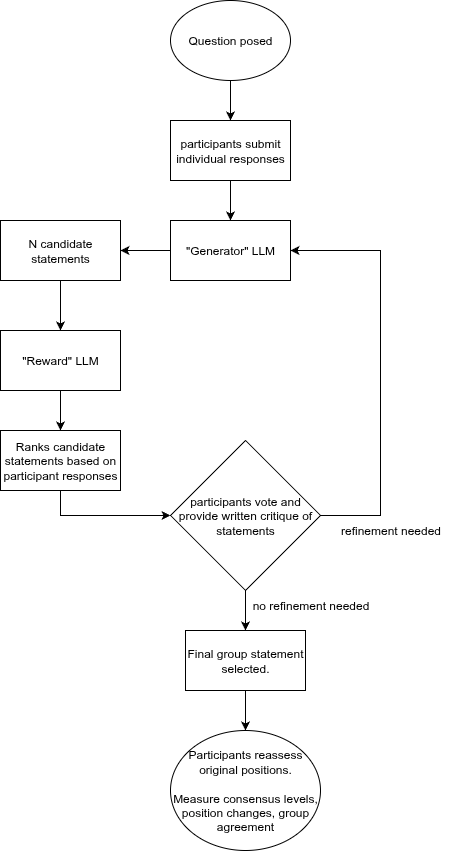

Drawing on Habermas’s ideas of communicative consensus, Google DeepMind researchers created the Habermas Machine, an LLM-powered consensus system that aims to help people reach consensus positions on contentious topics. It uses two fine-tuned LLMs based on Chinchilla. The first model generates potential consensus statements based on individual participants' written opinions and the second model predicts how well each participant will agree with these generated statements. Through several rounds of refinement based on participant feedback, the system produces group statements designed to satisfy the overall population to the greatest degree while respecting minority viewpoints. In tests with over 5,000 UK participants across multiple experiments, the Habermas Machine performed well. 56% of participants preferred AI-generated consensus statements over those created by humans, group agreement increased by an average of 8 percentage points, and participants were more likely to shift their positions toward consensus after the AI-mediated process. Third party evaluators also rated the AI statements higher for quality, clarity, fairness, and informativeness compared to human-mediated alternatives.

These forays into LLM powered consensus machines suggest, to optimists, that AI can find hidden middle ground between participants that initially seem to have irresolvably divergent views, while scaling discourse beyond what can be facilitated by humans.

The risks

AI powered consensus systems have also attracted criticism, mostly targeted at the idea that the LLM doesn’t really solve or circumvent the issues with deliberative democracy raised by Riker, Arrow and many others since, it just hides them in a futuristic black box, creating a kind of consensus theatre. The foundational problems have been pushed down the stack into the LLMs training data and algorithms, making them appear solved.

Some scholars have warned of “algocracy” (rule by algorithm), which might present as democracy but really limits deliberation and impose hidden constraints. Conflict may be a necessary component of true democracy, as it forces positions to be harshly stress-tested and defended. LLM-powered consensus systems don’t support conflict, they architect around it and replace it with data processing and linguistics, arguably preventing political growth. At the same time, interacting with an LLM rather than fellow humans prevents important human-to-human elements of deliberation such as building interpersonal empathy, trust and mutual respect.

Despite it’s name, the Habermas Machine uses algorithms to find a social choice that minimises disagreement, which arguably isn’t really deliberative. It isn’t encouraging participants to find compromise positions, it is simply iterating through candidate statements to find the one that is least repellent to the greatest number of participants. Consensus could be arising from linguistic optimisation rather than from challenge and deliberation. The fact that candidate position statements are being generated on the fly doesn’t change the underlying mechanism, which is still closer to preference aggregation rather than Habermas’s communicative rationality. LLM-powered consensus could even take us further away from Habermas by replacing human-to-human interactions with human-AI interactions, risking the humans in the system becoming increasingly like passive data providers than active participants, especially because there’s typically no fact-checking or guardrails to prevent conversations going off-topic.

It’s also possible that adding LLMs into the democratic process expands the attack surface for bad actors or opportunities for emergent negative outcomes. The more we are controlled remotely, the less likely we are to be able to express our free will, un-coerced. There’s also a related risk in leaders and their proxies censoring or promoting certain information from LLMs (preventing the electorate from being properly informed), shaping the tone and content of LLM responses or boosting self-serving interpretations of participant responses, allowing them the ‘lean on the scales’ for certain democratic choices. Since this can all happen inside an apparently neutral black box, it might be hard to detect. There’s a possibility of an infinite regress of Habermas machines each deciding who gets to set the political priors of the Habermas machine above.

There’s also the risk of “epistemic capture” where AI systems shape the knowledge and understanding of the public by creating and moderating the content we consume, and then also interpret and nudge the opinions we voice to AI via chats through the same lens, recursively reinforcing a certain worldview.

These criticisms reduce down to scepticism that there is a technological solution to a fundamentally human problem.

Designing consensus machines for smaller organisations

I think, cautiously, that there a lot of potential for consensus machines working in smaller ,more constrained contexts. I’d anticipate a big difference between a general purpose consensus machine designed to find agreement about arbitrary topics with participants representing the general population, and a consensus machine whose domain is restricted to a specific purpose, with a smaller population of selected participants. A good example is the consensus finding activities done at the Green Software Foundation. Typically, the aim is to come to consensus over the details of a technical standard or position about a specific technological or policy change. The motivation for exploring LLM consensus machines would be to improve the quality of the consensus forming process as well as enabling a small team of humans to scale their operations far beyond what they can achieve manually.

In this case, the constraints on general purpose consensus machines might be relaxed somewhat, as the participants are already self-selected as well-informed, often expert, practitioners in the relevant field and are usually participating with the explicit intention of deliberating to find a compromise consensus position. There are also opportunities for all participants to speak synchronously and make human to human connections. The population isn’t typically strongly polarised at the outset, and the risk of manipulation is usually low (although there may be business sensitivities and strategies that could incentivise manipulation in some cases, and this needs to be managed). This makes me think there might be a decent chance of some success.

Here are some questions that we’ll have to think hard about if we decide to start incorporating LLMs into our consensus process:

Can we safely assume the the participants are communicative actors or should we assume them to be strategic actors?

How can we balance between protecting against malicious gaming of the system and scaffolding free deliberation?

Riker would view any AI-generated consensus as arbitrary, whereas Habermas would evaluate it based on the quality of the deliberative process that was undertaken. How can we boost the quality of dialogue to strengthen the consensus position that emerges?

How can we test the biases of the model(s) and account for them?

Should we build in escape hatches from the LLM consensus, so that humans can take over when necessary? What markers could we use to identify the right moment to escape?

How can we ensure a consensus machine improves the quality as well as the speed and scale of the consensus forming process? What metrics could show us when we’re doing well and less well?